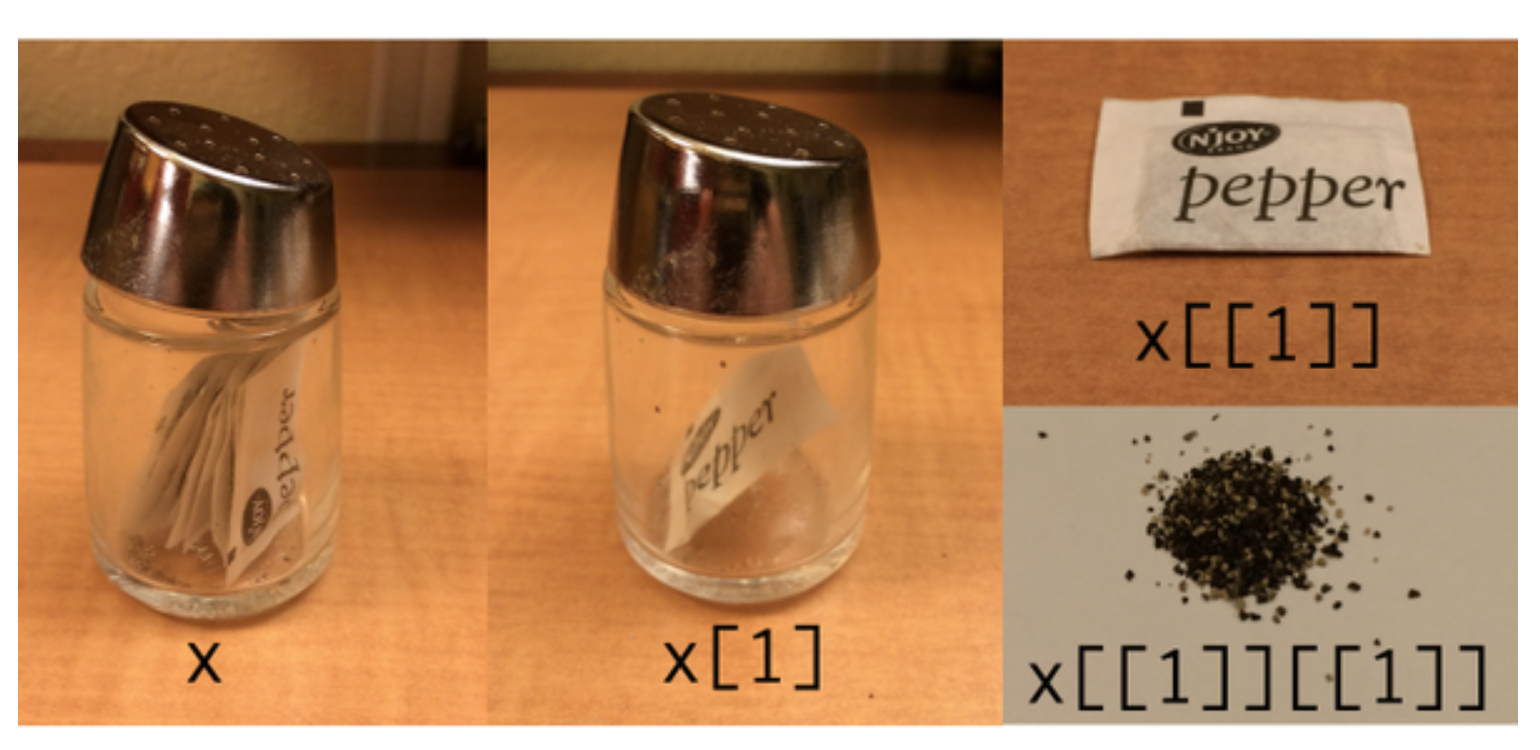

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # For Loops & Bootstrapping --- # The Problem - Copying and pasting code is not an efficient use of your time - Often you want to do the same thing but with different inputs: - Get the mean of a variable for 20 different groups - Plot different variables as your x-axis against the exact same y-axis - Do the exact same analysis and make the same plots for the levels of an independent variable (e.g., patients and controls) -- - In sum, you're trying to **iterate** (perform repeatedly) --- # How do we address this? In this class, we are going to talk specifically about `for loops`. Why? - They are *general purpose*. You will find them in nearly every single programming language. If you decide to not use `R` and instead go to `Python` or `Matlab` or whatever, you'll still come across them. - This is a fundamental component of programming. I would guess that you learn this within the first 2 weeks of CS 131. -- There are other ways to do this that are `R`-specific. We are NOT going to cover these (counterintuitive, I know). - the `apply` family of functions, including `lapply` - using the `purr` package from the `tidyverse` --- name: lists # Lists Lists are basically vectors but where every element can be a totally different data class. Ex: .code-small[ ```r myList <- list(6, head(iris), "hello world", c(1, 3, 5, 7, 9)) myList ``` ``` ## [[1]] ## [1] 6 ## ## [[2]] ## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species ## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa ## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa ## 5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa ## ## [[3]] ## [1] "hello world" ## ## [[4]] ## [1] 1 3 5 7 9 ``` ] --- # Lists You can also name the elements in your list: .code-small[ ```r myList <- list(Numberz = 6, DFs = head(iris), Chars = "hello world", VectorKing = c(1, 3, 5, 7, 9)) myList ``` ``` ## $Numberz ## [1] 6 ## ## $DFs ## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species ## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa ## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa ## 5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa ## ## $Chars ## [1] "hello world" ## ## $VectorKing ## [1] 1 3 5 7 9 ``` ] --- # Lists The weirdest thing about lists is accessing the elements within a list. Think of it like a book: - The element itself is like the chapter of a book - But there's a page that just says "Chapter 4" but doesn't contain any text - You need to tell `R` to go to the actual chapter -- We can do this with double brackets 👇 ```r myList[1] ``` ``` ## $Numberz ## [1] 6 ``` ```r myList[[1]] ``` ``` ## [1] 6 ``` --- # Lists Why does this matter? Say we wanted to take our number `6` from our list and add it to the number `12` ```r myList[1] + 12 ``` ``` ## Error in myList[1] + 12: non-numeric argument to binary operator ``` ```r myList[[1]] + 12 ``` ``` ## [1] 18 ``` --- # Lists are weird From Hadley Wickham, creator of `tidyverse`  --- name: fl # Now on to `for loops` ```r for (i in 1:some number) { do something } ``` *"For each element in 1 through ___, perform some function"* *"Perform the function contained in this for loop on every single element in some list of elements"* --- # `for loops` ```r for (i in 1:some number) { do something } ``` The important parts: - You can iterate over anything: rows of a data.frame, columns of a data.frame, lists, or simple 1-dimensional vectors. The `1:some number` portion are the elements you’re iterating over. If you wanted to do something 5 times, you could say `1:5`. Most of the time, we don’t know that second number, though. So we can use a function. `1:nrow(data.frame)` or `1:length(list)` or `1:length(vector)`. -- - The `i` stands for “each” and is the same type of `i` seen in equations. The top line then reads: “For each item/element in 1 through some number”. -- - The part between the curly brackets `{ }` is what you want to do (it’s the body of the for loop). --- # A Simple Example For each number in 1 through 10, print the following: *"(number) squared is (that number squared)"* So for the number 2, the output should be *"2 squared is 4"* The functions we are going to use are `print()` and `paste0()`. .code-small[ ```r for (i in 1:10) { print(paste0(i, " squared is ", i^2)) } ``` ``` ## [1] "1 squared is 1" ## [1] "2 squared is 4" ## [1] "3 squared is 9" ## [1] "4 squared is 16" ## [1] "5 squared is 25" ## [1] "6 squared is 36" ## [1] "7 squared is 49" ## [1] "8 squared is 64" ## [1] "9 squared is 81" ## [1] "10 squared is 100" ``` ] --- # Storing the output Is there any way for me to access any of the squared numbers from above? No! If you want to store the output of a loop (which in almost all cases we do), you need to **initialize** an empty object. This means make a blank object *before* running your loop that will contain your stored results. -- Let's run the same loop as last time, but this time let's store the squared numbers, rather than just printing out some lines. .code-small[ ```r squaredNumbers <- NULL for (i in 1:10) { squaredNumbers[i] <- i^2 } squaredNumbers ``` ``` ## [1] 1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81 100 ``` ] --- # Recap The basic steps of constructing a `for loop`: 1. Figure out what it is that you want to iterate through (numbers, columns of a data.frame, data.frames, a list, etc.) 2. Think about what you want the *output* to look like, and initialize an empty object that can store the output 3. Type out all of the steps within the body of the loop --- name: ex1 # Applied Examples What if you want to run the following models where the `Y` dependent variable stays the same, but the `X` independent variable changes? For this first example, let's say we only care about the `\(p\)`-value. - `lm(Sepal.Length ~ Sepal.Width, data = iris)` - `lm(Sepal.Length ~ Petal.Length, data = iris)` - `lm(Sepal.Length ~ Petal.Width, data = iris)` ``` ## Sepal.Length Sepal.Width Petal.Length Petal.Width Species ## 1 5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 2 4.9 3.0 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 3 4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2 setosa ## 4 4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2 setosa ## 5 5.0 3.6 1.4 0.2 setosa ## 6 5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4 setosa ``` --- # Applied Examples Thinking through what we need to happen: 1. We're iterating through specific columns of the `iris` data.frame -- so we need to get those column names into a form we can iterate through. 2. The output is a vector that contains `\(p\)`-values only 3. The body of the loop needs to contain the `lm()` functions --- # Applied Example 1 ```r varsToIterate <- colnames(iris)[2:4] sigValues <- NULL for (i in 1:length(varsToIterate)) { model <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ iris[,i], data = iris) model <- tidy(model) sig <- model[[2,5]] sigValues[i] <- sig } sigValues ``` ``` ## [1] 0.000000e+00 1.518983e-01 1.038667e-47 ``` --- # Applied Example 1 You can make comments within `for loops` ```r # get the column names in a format that we can iterate through varsToIterate <- colnames(iris)[2:4] # initialize an empty output vector sigValues <- NULL for (i in 1:length(varsToIterate)) { # run the model where i is the column that is varying model <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ iris[,i], data = iris) # the tidy function comes from the `broom` package model <- tidy(model) # find the p-value from the tidied model sig <- model[[2,5]] # store the p-value in the output sigValues[i] <- sig } # print the output sigValues ``` ``` ## [1] 0.000000e+00 1.518983e-01 1.038667e-47 ``` --- name: ex2 # Applied Example 2 Now, what if you want to store the entire output of the model, not just the `\(p\)`-value? The output of `tidy(model)` is a data.frame. So the result of our loop will now be a **list of data.frames**, rather than a vector of `\(p\)`-values. Note the double brackets in `modelList[[i]]`! ```r varsToIterate <- colnames(iris)[2:4] modelList <- list() for (i in 1:length(varsToIterate)) { model <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ iris[,i], data = iris) model <- tidy(model) modelList[[i]] <- model } ``` --- # Applied Example 2 ```r print(modelList) ``` ``` ## [[1]] ## # A tibble: 2 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 0 3.79e-17 0 1 ## 2 iris[, i] 1 6.43e-18 1.56e17 0 ## ## [[2]] ## # A tibble: 2 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 6.53 0.479 13.6 6.47e-28 ## 2 iris[, i] -0.223 0.155 -1.44 1.52e- 1 ## ## [[3]] ## # A tibble: 2 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 4.31 0.0784 54.9 2.43e-100 ## 2 iris[, i] 0.409 0.0189 21.6 1.04e- 47 ``` --- # Applied Example 2.1 Let's modify this slightly so that each output data.frame has a name associated with it (rather than 1, 2, 3) ```r varsToIterate <- colnames(iris)[2:4] modelList <- list() for (i in 1:length(varsToIterate)) { name <- paste0(varsToIterate[i]) model <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ iris[,i], data = iris) model <- tidy(model) modelList[[name]] <- model } ``` --- # Applied Example 2.1 ```r print(modelList) ``` ``` ## $Sepal.Width ## # A tibble: 2 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 0 3.79e-17 0 1 ## 2 iris[, i] 1 6.43e-18 1.56e17 0 ## ## $Petal.Length ## # A tibble: 2 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 6.53 0.479 13.6 6.47e-28 ## 2 iris[, i] -0.223 0.155 -1.44 1.52e- 1 ## ## $Petal.Width ## # A tibble: 2 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 4.31 0.0784 54.9 2.43e-100 ## 2 iris[, i] 0.409 0.0189 21.6 1.04e- 47 ``` --- # Applied Example 3 Let's do the same thing but with some modifications: - Let's also plot X & Y so we have a figure that corresponds with each model - Instead of the output being a list of the different models, what if we wanted the information from all of the models to be contained within a data.frame? -- When it comes to looping through plots, there are a few odd things: - the `sym()` function will take the quotes off of a string so that it can be evaluated properly - `!!` says "actually evaluate what a variable stands for". This will make sense when you see it in the code. --- name: ex3 # Applied Example 3 We want to store the model outputs AND a list of plots. So we need to initialize 2 things .code-small[ ```r modelDF <- data.frame() # for models plotList <- list() # for plots for (i in 1:length(varsToIterate)) { nameX <- paste0(varsToIterate[i]) # a character string for labels nameY <- "Sepal.Length" # doesn't change in the loop! # make the models model <- lm(Sepal.Length ~ iris[,i], data = iris) model <- tidy(model) # add a column that repeats whatever nameX is # for us, this will make it easier to keep track of what "i" is model$predictor <- rep(nameX, times = nrow(model)) # now bind the current model underneath the previous model # so that it's all contained within the same data.frame modelDF <- rbind(modelDF, model) # now make the plots nameXplot <- sym(varsToIterate[i]) plotList[[i]] <- ggplot(data = iris, aes(x = !! nameXplot, y = Sepal.Length)) + geom_point(color = "cornflowerblue") + labs(title = paste0(nameX, " by ", nameY), x = nameX, y = nameY) } ``` ] --- # Applied Example 3 ```r modelDF ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 6 x 6 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value predictor ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <chr> ## 1 (Intercept) 0 3.79e-17 0 1 e+ 0 Sepal.Width ## 2 iris[, i] 1 6.43e-18 1.56e17 0 Sepal.Width ## 3 (Intercept) 6.53 4.79e- 1 1.36e 1 6.47e- 28 Petal.Length ## 4 iris[, i] -0.223 1.55e- 1 -1.44e 0 1.52e- 1 Petal.Length ## 5 (Intercept) 4.31 7.84e- 2 5.49e 1 2.43e-100 Petal.Width ## 6 iris[, i] 0.409 1.89e- 2 2.16e 1 1.04e- 47 Petal.Width ``` --- # Applied Example 3 .pull-left[ .code-small[ ``` ## [[1]] ``` <img src="27-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-19-1.png" width="60%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ``` ## ## [[2]] ``` <img src="27-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-19-2.png" width="60%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] ] .pull-right[ .code-small[ ``` ## [[1]] ``` <img src="27-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-20-1.png" width="60%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] ] --- name: bs # Bootstrapping > to get oneself out of a situation using existing resources -- In statistics...any test or metric that uses random sampling with replacement -- - a bootstrapped mean - bootstrapped confidence intervals - bootstrap anything your heart desires! -- **SAMPLING _WITH_ REPLACEMENT** --- # Bootstrapping - Alternative to traditional NHST (considered a "resampling method") - Previously, we had to use equations, formulas, and a lot of assumptions to get our sampling distribution - But what if we don't know the theoretical sampling distribution or we can't verify it? -- - We build the sampling distribution empirically by random sampling with replacement from the sample - Easier to interpret and more robust because we're not relying on a bunch of assumptions/equations to estimate our sampling distribution -- we actually created the sampling distribution instead! - **robust** in statistics can mean different things. Here we're saying that it doesn't matter if a small thing changes in the dataset, because the bootstrapped mean will be resilient to those small changes. --- # Illustration Imagine you had a sample of 6 people that happen to live in NYC in the mid 1990's. Let's just say their names are Rachel, Monica, Phoebe, Joey, Chandler, and Ross. Maybe we have the height of each of these 6 individuals (in inches). But now let's say we want to get a sense of the average height in a person in their mid 20's in the 1990's in NYC. We can bootstrap the mean height. That is, we are going to draw from this group many samples of 6 people *with replacement*, each time calculating the average height of the sample. ``` ## [1] "Monica" "Chandler" "Phoebe" "Monica" "Chandler" "Phoebe" ``` ``` ## [1] 68.33333 ``` ``` ## [1] "Monica" "Rachel" "Ross" "Phoebe" "Phoebe" "Ross" ``` ``` ## [1] 68.66667 ``` ``` ## [1] "Monica" "Ross" "Chandler" "Joey" "Chandler" "Ross" ``` ``` ## [1] 70.83333 ``` ``` ## [1] "Phoebe" "Phoebe" "Joey" "Phoebe" "Phoebe" "Ross" ``` ``` ## [1] 69.16667 ``` ``` ## [1] "Phoebe" "Chandler" "Phoebe" "Phoebe" "Ross" "Joey" ``` ``` ## [1] 69.83333 ``` ``` ## [1] "Monica" "Chandler" "Monica" "Monica" "Chandler" "Phoebe" ``` ``` ## [1] 67.83333 ``` ``` ## [1] "Monica" "Ross" "Phoebe" "Monica" "Chandler" "Chandler" ``` ``` ## [1] 69.16667 ``` ``` ## [1] "Ross" "Joey" "Ross" "Ross" "Phoebe" "Phoebe" ``` ``` ## [1] 70.83333 ``` --- # Illustration ```r boot = 10000 friends = c("Rachel", "Monica", "Phoebe", "Joey", "Chandler", "Ross") heights = c(65, 65, 68, 70, 72, 73) sample_means = NULL for(i in 1:boot){ this_sample = sample(heights, size = length(heights), replace = TRUE) sample_means[i] = mean(this_sample) } mean(sample_means) ``` ``` ## [1] 68.85162 ``` --- # Illustration <img src="27-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-23-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # Bootstrapped Mean Let's say we have a sample of 100 participants that complete an IQ test. IQ tests typically have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. We want to get the mean IQ of our sample of 100 participants, but we want it to be a **robust** mean -- that is, we want to be pretty darn confident in our mean. What should we do? -- We can bootstrap our mean! And we can do that using a `for loop`: - *for each iteration of ## of iterations...* - Randomly sample FROM your current sample (so choose 100 from your 100) - But when choosing your new 100 data points, you are going to REPLACE each participant - This means Participant #1 could be chosen many times - On the next iteration (e.g., `i + 1`) do another round of choose 100 from your original 100 with replacement - etc. - After we run all of our iterations, then we will get the **mean of means** --- # Bootstrapping This whole process sounds like something you are already familiar with -- **sampling distributions** You can think of bootstrapping as building up your sampling distribution for whatever statistic you want. But instead of repeating your experiment 1000x, you're using a random sample of your current experiment. <center> <img src="27-slides_files/figure-html/fakeit.jpeg", width="30%"> </center> --- # Bootstrapped Means Example ```r iqs ``` ``` ## [1] 96 106 160 115 117 164 127 75 92 100 150 124 125 116 96 167 128 54 134 ## [20] 99 81 106 82 91 94 62 138 118 79 151 126 104 140 139 138 134 130 111 ## [39] 104 102 92 107 75 178 149 79 101 99 136 110 ``` --- # Bootstrapped Means Example ```r bsMeans <- NULL for (i in 1:100) { subsample <- sample(x = iqs, size = 50, replace = T) bsMeans[i] <- mean(subsample) } ``` --- # Bootstrapped Means Example Let's look at our vector of means .code-small[ ```r bsMeans ``` ``` ## [1] 108.24 116.12 103.58 110.66 119.66 111.28 124.18 114.98 115.40 114.98 ## [11] 110.76 116.42 113.02 111.06 112.32 108.14 111.30 115.70 115.96 121.50 ## [21] 112.78 110.96 108.40 108.22 122.12 108.84 119.16 118.40 114.32 112.78 ## [31] 114.36 113.78 117.92 121.16 112.54 116.14 108.82 120.72 115.00 116.30 ## [41] 112.56 111.24 112.28 111.98 107.18 114.52 114.58 113.20 112.62 114.42 ## [51] 122.10 117.58 107.96 111.52 117.52 107.58 107.36 115.54 109.72 115.74 ## [61] 116.36 114.90 112.56 110.34 112.04 111.72 110.42 114.38 119.72 115.62 ## [71] 116.48 118.86 119.82 114.64 113.00 116.86 109.86 114.36 109.26 115.66 ## [81] 108.84 116.18 113.70 118.86 111.24 112.08 108.12 119.14 119.12 111.92 ## [91] 113.32 113.90 120.70 121.54 108.76 107.96 107.82 108.14 115.66 111.90 ``` ] --- # Bootstrapped Means Example Now, get the mean of our vector of means...this is our **bootstrapped mean** ```r mean(bsMeans) ``` ``` ## [1] 113.8094 ``` -- When I made these fake IQ scores, I set the "true" population mean to be 113. Our mean of the original sample was `mean(iqs)` = **114.02** Our bootstrapped mean is `mean(bsMeans)` = **113.8094** -- The bootstrapped mean is closer to the true population mean -- it's more robust, and therefore we trust it more. --- # What can you bootstrap? Any statistic! - central tendency (means, medians, modes) - dispersion (variances, standard deviations) - other estimates (confidence intervals, reliability coefficients, correlations, etc.) Models! - on each iteration where you draw with replacement, run your model - then take the mean of all the coefficients (like regression coefficients, t-values, etc.) **_what *can't* you bootstrap?_** --- # Final Thoughts - Code is supposed to make your life EASIER. Use `for loops` to your advantage! That means if you find yourself copying/pasting the same thing a billion times with only minor changes, there’s likely a much simpler way of doing everything you need all in one go. - check out nested `if/else` statements in the practice set! - for `R` specific functions, check out the `lapply()` function and the `purr` package - when you are first writing your `for loop` and testing things, use really small iterations; once it's working properly, then you can run a ton of iterations - Bootstrapping is just a `for loop`. You can bootstrap anything your heart desires. - The biggest piece of advice I have is to think carefully about what you want the end result to look like and then work backwards. Don’t just start doing stuff to your dataset because you think that’s what your supposed to do. Think “in order to make this plot, I need my data in this particular format, what do I need to do to get there?”