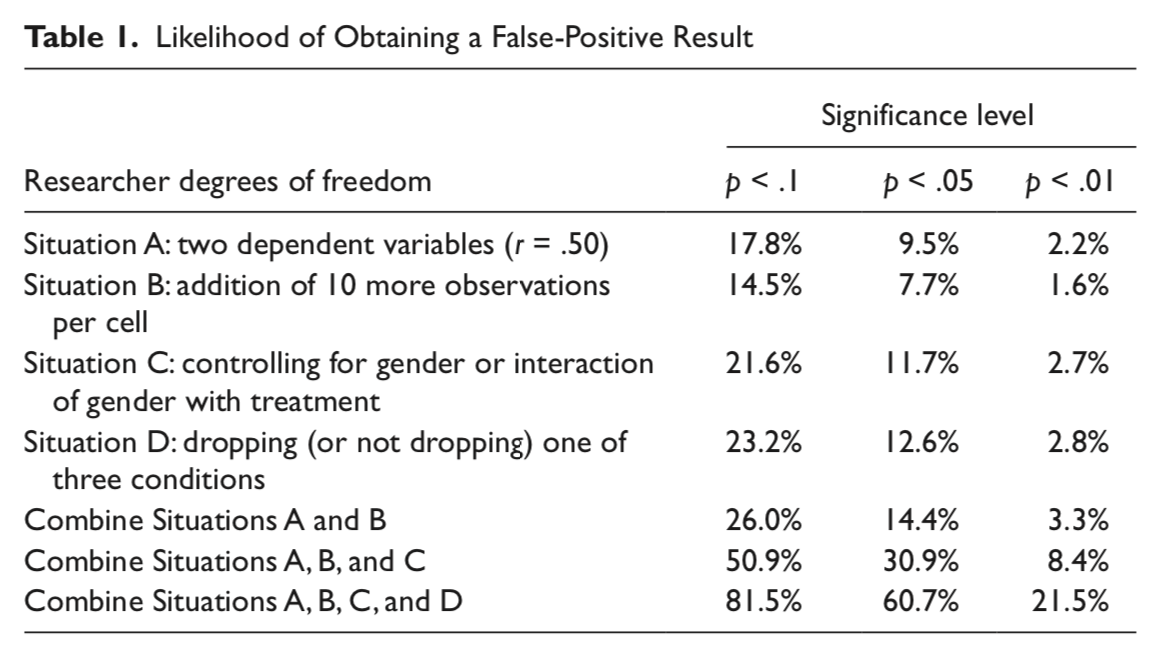

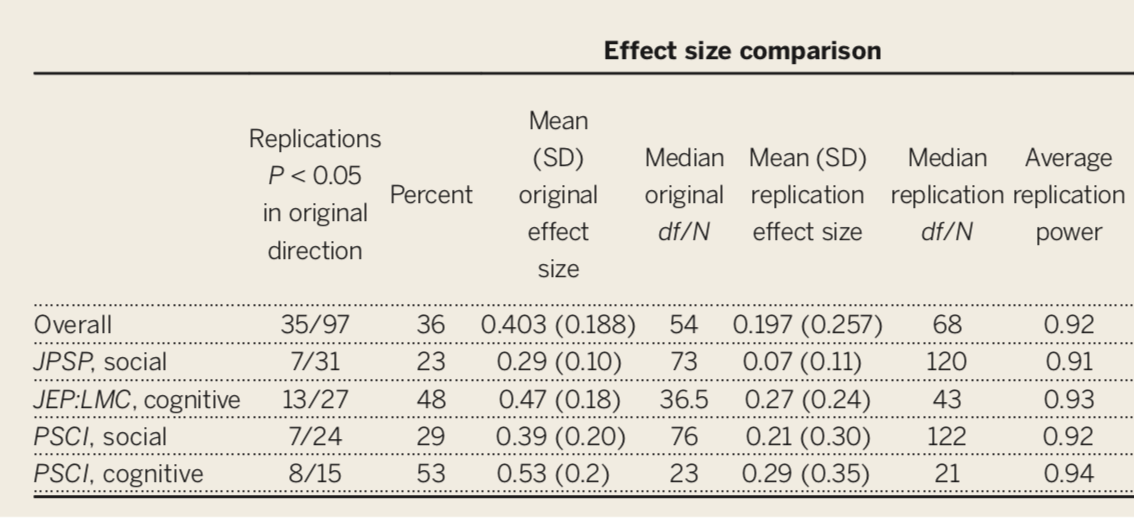

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Power Plus --- # Recap - How we utilize our sampling distributions to make probability statements about the comparison across means (*t*-tests, ANOVA etc.) - The NHST process --- # Today - Confidence Intervals - *p*-values redux - Power - Problems with NHST --- name: ci # Confidence Intervals The sampling distribution of the mean has variability, represented by the SEM, reflecting uncertainty in the sample mean as an estimate of the population mean. The assumption of normality allows us to construct an interval within which we have good reason to believe a population mean will fall: $$\bar{X} - (1.96\times SEM) \leq \mu \leq \bar{X} + (1.96\times SEM) $$ ??? Sampling distributions are normally distributed --- # Confidence Intervals $$\bar{X} - (1.96\times SEM) \leq \mu \leq \bar{X} + (1.96\times SEM) $$ - This is referred to as the **95% confidence interval (CI)** - The 95% CI is sometimes represented as: `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [1.96\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` --- # Confidence Intervals Confidence Intervals are estimates of **precision** If you have a very wide CI, it means there's a very large range that would be reasonable for that true population parameter. Not what you'd call "precise". If you have a narrower CI, there's a much smaller range that would be reasonable for that true population parameter. More precise. -- If you are doing a *t*-test, and your CI includes the number 0, what does that mean in terms of significance? --- .left-column[ .small[ ### The `\(t\)` The normal distribution assumes we know the population mean and standard deviation. But we don’t. We only know the *sample* mean and standard deviation, and those have some uncertainty about them. That uncertainty is reduced with large samples, so that it's “close enough” to the normal. In small samples, the `\(t\)` distribution is better. ] ] <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-1-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- # `\(t\)` distribution - The primary difference between the normal distribution and the `\(t\)` distribution is the fatter tails - This produces wider **confidence intervals** - The penalty we have to pay for our ignorance about the population - The form of the confidence interval remains the same. We simply substitute a corresponding value from the `\(t\)` distribution (using df = `\(N - 1\)`). `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [1.96\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` `$$CI_{95} = \bar{X} \pm [t_{.975, df = N-1}\frac{\hat{\sigma}}{\sqrt{N}}]$$` --- # Confidence Intervals What does it NOT mean? - There is a 95% probability that the true mean lies inside the confidence interval -- What it *actually* means: - If we carried out random sampling from the population a large number of times... - and calculated the 95% confidence interval each time... - then 95% of those intervals can be expected to contain the population mean. -- [Interactive Example](https://rpsychologist.com/d3/ci/) --- # Examples .small[ In the past, my classroom exams (aggregating over many classes) have a mean of 90 and a standard deviation of 8. My next class will have 100 students. What range of exam means would be plausible if this class is similar to past classes (comes from the same population)? ] .code-small[ ```r M = 90 SD = 8 N = 100 sem = SD/sqrt(N) ci_lb_z = M - sem * qnorm(p = .975) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qnorm(p = .975) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 88.43203 91.56797 ``` ```r ci_lb_z = M - sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 88.41263 91.58737 ``` ] --- ## Examples .small[ I give a classroom exam that produces a mean of 83.4 and a standard deviation of 10.6. A total of 26 students took the exam. What is the 95% confidence interval around the mean? ] ```r M = 83.4 SD = 10.6 N = 26 sem = SD/sqrt(N) ci_lb_z = M - sem * qnorm(p = .975) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qnorm(p = .975) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 79.32557 87.47443 ``` ```r ci_lb_z = M - sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) ci_ub_z = M + sem * qt(p = .975, df = N-1) print(c(ci_lb_z, ci_ub_z)) ``` ``` ## [1] 79.11857 87.68143 ``` --- # Recap Confidence intervals are estimates of **precision** They tell you nothing about the strength of an association If it overlaps with 0, not significant. But other than that, it can't tell you much in the way of significance. --- name: p # Significance We set an `\(\alpha\)` level. This is the rate at which we are OK making a false positive (more on this later). - By convention, in Psychology, `\(\alpha = .05\)` or `\(\alpha = .01\)` -- This alpha is our cutoff rate. If our *p*-value is smaller than our `\(\alpha\)`, we claim "Significance!" So what does the `\(p\)`-value actually mean? --- # *p*-values **The probability of getting a test statistic _or more extreme_ given that the null hypothesis is true** -- Last lecture, we went through an example of `\(z\)`-test. We wound up with a `\(z\)`-statistic of `\(-2.18\)` and came out with a `\(p\)`-value of `\(.029\)`. - H0 = difference in applicant means between men and women is 0 (no difference) - HA = difference in applicant means between men and women is not 0 (there is a difference) -- "The probability that the average female applicant's score would be at least 2.18 units away (or even further away, more negative) from the average male score, given that we expect no difference between mean, is `\(.029\)`." It's very, very unlikely to be the case that we would get a score of `\(-2.18\)` or even more extreme ( `\(-3\)` etc.), if these means come from the same population distribution. It's so unlikely and rare, in fact, that we say "these are significantly different from one another" --- # A *p*-value DOES NOT: - Tell you that the probability that the null hypothesis is true. - Prove that the alternative hypothesis is true. - Tell you anything about the size or magnitude of any observed difference in your data. - Tell you anything about the precision of your estimate. --- # More on *p*-values Is that a really low probability? -- Before you test your hypotheses -- ideally, even before you collect the data -- you have to determine how low is too low. Researchers set an alpha ( `\(\alpha\)` ) level that is the probability at which you declare your result to be "statistically significant." How do we determine this? -- Consider what the p-value means. In a world where the null ( `\(H_0\)` ) is true, then by chance, we'll get statistics in the extreme. Specifically, we'll get them `\(\alpha\)` proportion of the time. So `\(\alpha\)` is our tolerance for False Positives or incorrectly rejecting the null. --- name: power # Errors In hypothesis testing, we can make two kinds of errors. | | Reject `\(H_0\)` | Do not reject | |------------:|:----------------:|:----------------:| | `\(H_0\)` True | Type I Error | Correct decision | | `\(H_0\)` False | Correct decision | Type II Error | Falsely rejecting the null hypothesis is a **Type I error**. Traditionally this has been viewed as particularly important to control at a low level (akin to avoiding false conviction of an innocent defendant). --- # Errors In hypothesis testing, we can make two kinds of errors. | | Reject `\(H_0\)` | Do not reject | |------------:|:----------------:|:----------------:| | `\(H_0\)` True | Type I Error | Correct decision | | `\(H_0\)` False | Correct decision | Type II Error | Failing to reject the null hypothesis when it is false is a **Type II error**. This is sometimes viewed as a failure in signal detection. --- # Errors In hypothesis testing, we can make two kinds of errors. | | Reject `\(H_0\)` | Do not reject | |------------:|:----------------:|:----------------:| | `\(H_0\)` True | Type I Error | Correct decision | | `\(H_0\)` False | Correct decision | Type II Error | Null hypothesis testing is designed to make it easy to control Type I errors. We set a minimum proportion of such errors that we would be willing to tolerate in the long run. This is the significance level ( `\(\alpha\)` ). By tradition this is no greater than .05. --- # Errors In hypothesis testing, we can make two kinds of errors. | | Reject `\(H_0\)` | Do not reject | |------------:|:----------------:|:----------------:| | `\(H_0\)` True | Type I Error | Correct decision | | `\(H_0\)` False | Correct decision | Type II Error | Controlling Type II errors is more challenging because it depends on several factors. But, we usually DO want to control these errors. **Power** is the probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis. --- ### Some Greek letters `\(\alpha\)` -- The rate at which we make Type I errors, which is the same `\(\alpha\)` as the cut-off for `\(p\)` -values. `\(\beta\)` -- The rate at which we make Type II errors. `\(1-\beta\)` -- statistical power. Note that these are all probability statements; not abstract ideas --- Controlling Type II errors is the goal of power analysis and must contend with four quantities that are interrelated: - Sample size - Effect size - Significance level ( `\(\alpha\)` ) - Power When any three are known, the remaining one can be determined. Usually this translates into determining the power present in a research design, or, determining the sample size necessary to achieve a desired level of power. We must specify a specific value for the alternative hypothesis to estimate and control Type II errors. --- Suppose we have a measure of social sensitivity that we have administered to a random sample of 20 psychology students. This measure has a population mean ( `\(\mu\)` ) of 100 and a standard deviation ( `\(\sigma\)` ) of 20. We suspect that psychology students are more sensitive to others than is typical and want to know if their mean, which is 110, is sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis that they are no more sensitive than the rest of the population. We would also like to know how likely it is that we could make a mistake by concluding that psychology students are not different when they really are: A Type II error. --- .left-column[ .small[ We begin by defining the location in the null hypothesis distribution beyond which empirical results would be considered sufficiently unusual to lead us to reject the null hypothesis. We control these mistakes (Type I errors) at the chosen level of significance ( `\(\alpha = .05\)` ). ] ] <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/student null-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ??? ### How do we figure out where this region is? Start with our `\(\alpha\)` level (.05) Given our distribution parameters, what Z-value corresponds to .05 above that line mu = 100 x = 110 s = 20 n = 20 sem = `\(\frac{20}{\sqrt{20}}\)` = 4.47 z = 1.64 --- .pull-left[ `$$\text{Critical Value} = \mu_0 + Z_{.95}\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{N}}$$` ```r qnorm(.95) ``` ``` ## [1] 1.644854 ``` `$$\text{Critical Value} = 100 + 1.645\frac{20}{\sqrt{20}} = 107.4$$` What if the null hypothesis is false? How likely are we to correctly reject the null hypothesis in the long run? ] .pull-right[ <p> </p> <p> </p> <p> </p> <p> </p> <p> </p> <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-5-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] --- .left-column[ .small[ To determine the probability of a Type II error we must specify a value for the alternative hypothesis. We will use the sample mean of 110. In the long run, if psychology samples have a mean of 110 ( `\(\sigma = 20\)`, `\(N = 20\)` ), we will correctly reject the null with probability of .72 (power). We will incorrectly fail to reject the null with probability of .28 ( `\(\beta\)` ). ] ] <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/student null and alt-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- .pull-left[ <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-7-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> Once the critical value and alternative value is established, we can determine the location of the critical value in the alternative distribution. ] -- .pull-right[ `$$Z_1 = \frac{CV_0 - \mu_1}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{N}}}$$` `$$Z_1 = \frac{107.4 - 110}{\frac{20}{\sqrt{20}}} = -.59$$` The proportion of the alternative distribution that falls below that point is the probability of a Type II error (.28); power is then .72. ```r pnorm(-.59) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.2775953 ``` ] --- The choice of 110 as the mean of `\(H_1\)` is completely arbitrary. What if we believe that the alternative mean is 115? This larger signal should be easier to detect. .pull-left[ <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-10-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ `$$Z_1 = \frac{107.4 - 115}{\frac{20}{\sqrt{20}}} = -1.71$$` ```r 1-pnorm(-1.71) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.9563671 ``` ] --- What if instead we increase the sample size? This will reduce variability in the sampling distribution, making the difference between the null and alternative distributions easier to see. .pull-left[ <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-13-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ `$$\text{CV} = 100 + 1.645\frac{20}{\sqrt{40}} = 105.2$$` `$$Z_1 = \frac{105.2 - 110}{\frac{20}{\sqrt{40}}} = -1.52$$` ```r 1-pnorm(-1.52) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.9357445 ``` ] --- What if we decrease the significance level to .025? <p> </p> .pull-left[ <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-16-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ That will move the critical value: `$$CV_0 = 100 + 1.96[\frac{20}{\sqrt{20}}] = 108.8$$` `$$Z_1 = \frac{108.8 - 110}{\frac{20}{\sqrt{20}}} = -.28$$` ```r 1-pnorm(-.28) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.6102612 ``` ] I strongly recommend playing around with different configurations of `\(N\)`, `\(\alpha\)` and the difference in means ( `\(d\)` ) in this [online demo](https://rpsychologist.com/d3/NHST/). --- ### How can power be increased? .pull-left[ <img src="23-slides_files/figure-html/unnamed-chunk-18-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> ] .pull-right[ `$$Z_1 = \frac{CV_0 - \mu_1}{\frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{N}}}$$` - increase `\(\mu_1\)` - decrease `\(CV_0\)` - increase `\(N\)` - reduce `\(\sigma\)` ] --- # Most published research is underpowered!!! - We strive for power of ~.80; making Type II errors 20% of the time - We are often farrrrrrrrrrr below this - Reproducibility Crisis - It's like, *super* bad --- # NHST and Good Science > "The textbooks are wrong. The teaching is wrong. The seminar you just attended is wrong. The most prestigious journal in your scientific field is wrong." – Ziliak and McCloskey (2008) > "... surely the most bone-headedly misguided procedure ever institutionalized in the rote training of science students" – Rozeboom (1997) > "What's wrong with [NHST]? Well, among many other things, it does not tell us what we want to know, and we so much want to know what we want to know that, out of desperation, we nevertheless believe that it does!" – Cohen (1994) --- ### What kind of mess have we got ourselves into? - `\(p < .05\)` as a condition for publication - Publication as a condition for tenure - Novelty as a condition for publication in top-tier journals - Institutionalization of NHST - High public interest in psychological research - Unavoidable role of human motives: fame, recognition, ego --- ### What kind of science have we produced? - `\(p < .05\)` as a primary goal; dichotomous thinking (based on `\(p\)` ): research either “succeeds” or “fails” to find the expected difference - Publication bias: “Successes” are published, “failures” end up in file drawers - Overestimation of effect size in published work - Underestimation of complexity (why did the failures occur?) - Underestimation of power - Inability to replicate - Settling for vague alternative hypotheses: “We expect a difference” --- ### Focusing on `\(p\)` -values Imagine rolling a die. - What’s the probability you roll a 2? - `\(P(2) = 1/6 = 16.7\%\)` - If you roll the die twice, what’s the probability that you get a 2 at least once? `\(30.6\%\)` - If you roll the die 5 times, what’s the probability that you get a 2 at least once? `\(59.8\%\)` Roll the die enough times, and you'll get a 2 eventually. Significance testing when the null is true is like rolling a 20-sided die. --- ## False Positive Psychology [Simmons et al. (2011)](23-slides_files/figure-html/Simmons_etal_2011.pdf) pointed out that each study is not a single roll of the die. Instead, each study, even those with a single statistical test, might represent many rolls of the die. - **Researcher degrees of freedom:** Decisions that a researcher makes that change the statistical test. - Examples: - Additional dependent variabiles - Tests with and without covariates - Data peeking (testing effect as data comes in and stopping when result is significant) --- Each time I see how a decision affected my result, I am rolling the dice again.  ??? from Simmons et al: The table reports the percentage of 15,000 simulated samples in which at least one of a set of analyses was significant. Observations were drawn independently from a normal distribution. Baseline is a two-condition design with 20 observations per cell. Results for Situation A were obtained by conducting three t tests, one on each of two dependent variables and a third on the average of these two variables. Results for Situation B were obtained by conducting one t test after collecting 20 observations per cell and another after collecting an additional 10 observations per cell. Results for Situation C were obtained by conducting a t test, an analysis of covariance with a gender main effect, and an analysis of covariance with a gender interaction (each observation was assigned a 50% probability of being female). We report a significant effect if the effect of condition was significant in any of these analyses or if the Gender × Condition interaction was significant. Results for Situation D were obtained by conducting t tests for each of the three possible pairings of conditions and an ordinary least squares regression for the linear trend of all three conditions (coding: low = –1, medium = 0, high = 1). --- ### *p*-hacking **_p_-hacking:** collecting or selecting data or statistical analyses until non-significant results become significant. Prior to 2011, this was common practice. In fact, it was often taught as best practices. - "Explore your data." - "Understand your data." - "Test sensitivity..." We should recognize now that this inflates Type I error. --- The publication of this, following the claim by [Ioannidis (2005)](23-slides_files/figure-html/Ioannidis_2005.pdf) that as many as half of published findings are false prompted researchers to take a second look at the "knowns" in our literatures. If we can demonstrate these "known" effects, then we're ok. Our effects are most likely true. -- And if that had happened, we probably wouldn't have two lectures in this class dedicated to problems with NHST and how to address them. --- The inability to replicate published research has been viewed as especially troubling. - This has been a long-standing concern, but the poster child is undoubtedly ["Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science"](23-slides_files/figure-html/OSC_2015.pdf) by the Open Science Collaboration (Science, 2015, 349, 943). --- Only 36% of the studies were replicated, despite high power and claimed fidelity of the methods.  --- ### Why is it so hard to replicate? - Poor understanding of context necessary to produce most effects - We do not recognize the boundary conditions of effects especially when the limiting conditions are kept constant - Incomplete communication of the necessary conditions - Akin to reading just the first few ingredients for a recipe and then trying to duplicate the dish. --- ### Why is it so hard to replicate? Sparse communication fosters belief by others that effects are simpler and easier to produce than they really are. The reality is that key elements have been left out: - specific methodological or analytic details - and the tests run before and after the ones that were published. --- name: open ## What can we do? .pull-left[ **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** ] .pull-right[ **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** **BE TRANSPARENT** ] --- # R & RMarkdown Using scripts and `.Rmd` files is a great way to get you on the path towards open science! When you publish a paper, you now will likely need to publish your code. And with markdown, you can annotate it properly to let the reader know exactly what you did *and why you did it* Don't be your own worst collaborator... --- class: inverse, center # Back. Up. Your. Code. --- # Version control with Git - **Git** is a version control system. Think Microsoft Track Changes for your code - Allows multiple collaborators to contribute to the same project - If you are going into data science (outside of academia), you 100% need to know this to get hired - If you are staying in academic research, you 99% need to know this for your own sanity --- # GitHub - **GitHub** is one site that facilitates the use of Git - Repositories can be private or public -- allows you to share your work with others - GitHub also plays well with Markdown language (as in RMarkdown) - Pair GitHub with R to make websites - This is where `R Projects` becomes really handy. Ask me more about them, and check this out if you're interested: [happy git with r](https://happygitwithr.com/) --- class: inverse # Next time... Moving towards relationships with correlations & regression